Northern Visions

More than thirty-seven million people live in Canada, and very few of them will ever visit the Far North. Clustered in towns and cities in the southern portions of the country, their vision of the Arctic regions comes only from photographs, videos, or works of art.

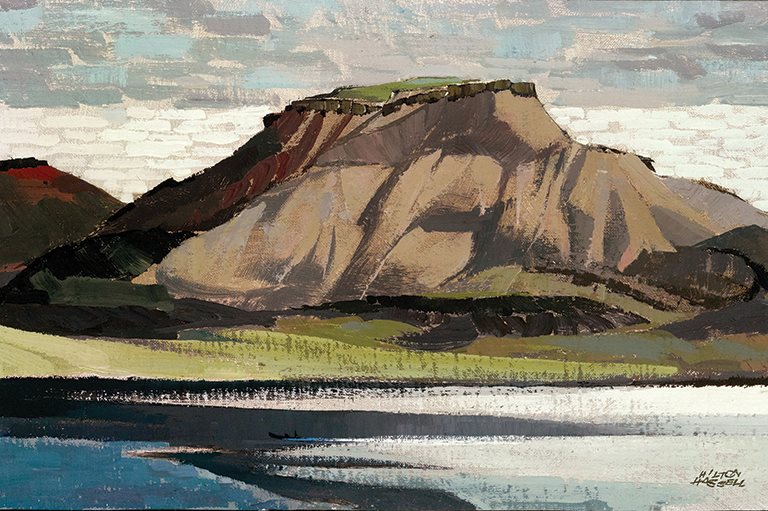

In 1974, a Canadian artist inspired by earlier landscape paintings by members of the Group of Seven travelled by ship through the Far North. Hilton Hassell’s voyage aboard the Fednav Limited ship MV Tundraland resulted in a burst of creativity and the production of a host of stunning landscape paintings as well as documentary-style photographs depicting the region’s places and peoples.

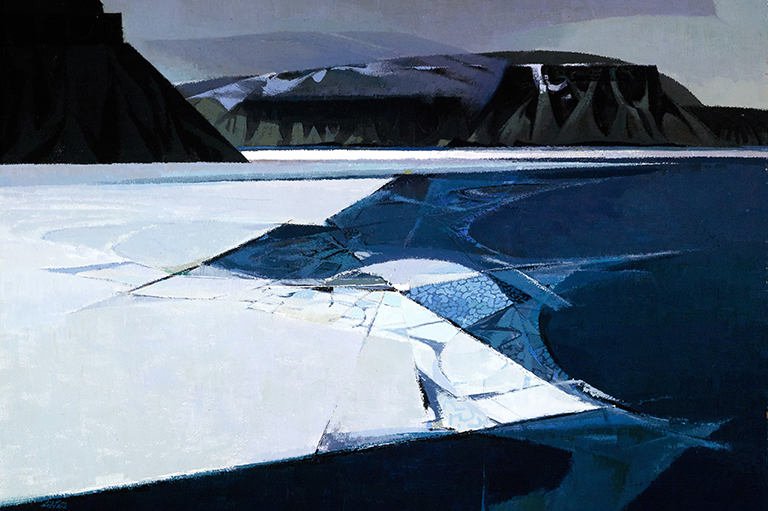

The voyage took Hassell to Maarmorilik in Greenland and to Arctic Bay, Pond Inlet, and Grise Fiord in what is today Nunavut. He then travelled past Devon Island, through Jones Sound and Hell Gate, and all the way to Axel Heiberg Island and Eureka, at 80° North on Ellesmere Island. Many of the smaller paintings he produced were made aboard the ship, while the larger pictures were created later in his studio, working from sketches he created during his journey.

All the paintings created during that 1974 voyage were subsequently purchased by Fednav (then known as Federal Commerce & Navigation), which today showcases the artworks in its offices around the world.

Hassell returned to the Arctic for another voyage in 1977 and died three years later at the age of seventy, leaving behind a legacy of evocative Arctic landscapes.

In 1994, John Weale, a vice-president of Fednav, published Patterns to Infinity, a book about Hassell’s northern journeys. Canada’s History editor-in-chief Mark Collin Reid spoke with Weale about Hassell’s enduring legacy.

Why do you think some critics diminished or dismissed his work, as you mention, by saying it demonstrates “smooth skills and well-tried tricks”?

Well, that’s an interesting question. Hassell had started out as a commercial artist, a profession that requires an ability to work quickly and within a convention dictated by a particular context. But when he left that métier and starting working as a serious artist, he would hardly abandon his technical ability. I think this sort of criticism is rather superficial and unpersuasive.

Hassell has said that when he looks at a landscape “of trees, groups of houses or cliff formations” he sees them begin to “link and form” into a design. How do you think this vision has influenced or affected his Arctic paintings?

Hassell was always reluctant to talk about his work; he wanted the pictures to speak for themselves. But I do think that this remark captures the essence of his Arctic paintings, and especially those without any sign of human activity. One of the paintings of Norwegian Bay, depicting a broad field of puddled ice, is titled Patterns to Infinity— and in a way that says it all. One aspect of his work that may deserve mention here is the variety that he manages to achieve within a fairly limited — and deliberately chosen — range of colours; the atmosphere created by his Newfoundland or Irish pictures is quite different from his Arctic work. Another interesting facet is the economy of line and shading in his pencil sketches.

Unlike some artists, Hassell seemed to prefer not to overtly explain the meaning behind his art. What does that say to you about the personality behind the paintbrush?

At least in public, I think he was almost reclusive when it came to speaking about his art, which he obviously took very seriously. But I don’t think I can really say much beyond that, because I never met him. He clearly worked decisively and quickly, and that may suggest a fairly firm and confident personality.

After Hassell’s first voyage aboard the Tundraland, Fednav decided to purchase his entire collection of Arctic paintings. What inspired that decision?

I wasn’t there at the time, so I can only speculate; but I think it was a natural reaction to seeing the effect of the whole group in one place — especially given the circumstances of its creation. So far as I know, the arrangement had been that the company would pay for Hassell’s travel and keep, and in return would have first refusal to purchase the resulting artwork at his asking price. Hassell went north again a few years later, and Fednav also bought some of the large paintings which originated on those trips.

What impresses you the most about Hassell’s paintings?

I think their freshness and sense of place. As you might say, they wear well!

You published Patterns to Infinity as a way of showcasing Hassell’s work during his Arctic voyages. Why was it important for you to share his story with the wider Canadian audience?

That was the fiftieth anniversary of Fednav’s incorporation. We wanted to produce something to mark the occasion for our employees and customers which was unique to the company, something typically Canadian but not too ostentatious or self-promoting. We were able to borrow his journal and also his sketches and photographs from his family, and so we had enough material to present an interesting narrative in a manageable format. (As you may have noticed, we had the book printed locally: That was a conscious decision.)

Hassell seems to have somewhat divided his critics, with some praising his vision of the Far North and others saying that his paintings were more focused on technique than on adding something new or unique to the art form. How do you see Hassell’s legacy? And, how do you hope Canadians remember him and his work?

I may be a bit prejudiced, but I do believe his work will in due course gain greater attention and appreciation. Although he certainly went up north for other patrons or sponsors besides Fednav, many of those paintings, like ours, have remained in private hands, and as a result, his pictures may not have had as much exposure as they deserve. One day — I hope quite soon — Hilton Hassell’s time will come!

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!